User control over services as a precondition for self-determination

Adolf D. Ratzka, Ph.D.

www.independentliving.org/ratzka.html

Independent Living Institute, Sweden

www.independentliving.org

In the 40 years of my life with a disability I have had assistance with the activities of daily living such as getting up in the morning, getting bathed and dressed. I have lived in residential institutions in Germany, used community-based municipal homehelp in Sweden and had cash payments to hire personal assistants in California and in Stockholm.I studied service delivery systems professionally - I am a research economist by training - and personally by trying to live a life with work, family, travel and interests, in different countries, often with the help of services and often despite the services.

I am active in the Independent Living Movement where we work for self-determination, self-respect and equal opportunities and against the medicalization of disability. We are full citizens, not patients and objects of care.

I am with the Independent Living Institute where we spread information and design and implement pilot projects to improve our opportunities for self-determination. Typically, these pilot projects complement existing public services. (1)

Universal Design vs. individualized support services

Some people argue that a completely accessible society would make any special services for persons with disabilities unnecessary. All would have equal opportunities, earn a living and support themselves. This is an interesting thought but not the reality. People with my extensive personal assistance needs, for example, cannot reasonably be expected to earn enough to pay for their services. But the argument suggests a relationship between the way society is designed and our needs of support services.

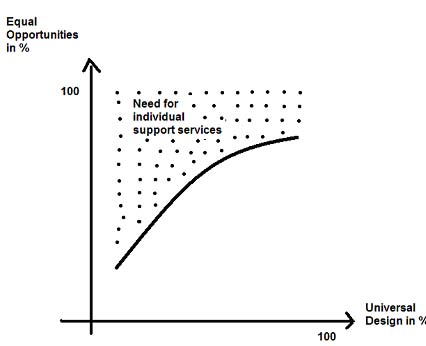

Diagram 1. Need for individual support services as function of Universal Design

In Diagram 1 equal opportunities for all members of society are on the vertical axis. On the horizontal axis is the degree to which the man-made environment - buildings, transportation, communications - has been built according to the Universal Design principle, i.e. equal access for all individuals has been the most important design and construction criterion. (2)

As I see it, the more Universal Design, the closer we get to equal opportunities for all citizens. But beyond a point there is only slight improvement in our opportunities. For example, an accessible bus down the street helps greatly, but if I do not have somebody to help me get up in the morning, I still cannot get to work. Even with the most accessible infrastructure some of us will always need individualized support services to compensate general solutions that can never completely meet all individual needs.

Procrustean services

I see two distinct service delivery models. They differ in their assumptions about the people they are to serve and in the degree of user empowerment.

Procrustes in Greek mythology offered his bed to tired travelers. Those who were too short, he would stretch until they fit. Those who were too long, he shortened with an ax. His policy was "ONE size fits ALL - with a little help."

Today, we still see many services that resemble Procrustes' approach:

- the services assume that all users have identical needs, tastes and preferences.

- users have no choice. "Take it or leave it!"

- the services force individuals to adapt themselves to fit the planners' assumptions

- the services empower users as little as Procrustes empowered his victims.

Example 1: community-based municipal home help services

In the 1970´s I used community-based municipal homehelp services in Stockholm. City employees came to me in the morning to help me get ready for the day. I could not choose the workers who were often late, uninterested, and incompetent. I was lucky, if they came at all. At night, two workers would make their rounds from one client to the next in a predetermined order. They would start with older people who had to go to bed at 5 o'clock in the afternoon. The night patrol, as they were called, was rarely on time and going out in the evening was risky, if I wanted to sleep that night in bed. I had no choice but to adapt my lifestyle to the service.

Somebody else made the decisions, I as the user was the smallest cog in the machinery. But even if there had been administrators who understood my needs, it would have been impossible for the system to accommodate people who wanted to go to bed as they pleased or to guarantee female staff to women who wanted female workers for assistance with intimate physical needs. The system was as flexible as a railroad, as efficient as a steam roller in flattening out differences in lifestyle among its users. (2)

Example 2: special transportation services for people with disabilities

Another example of the Procrustes school of thought in service delivery are special transportation services for people who cannot use ordinary public transportation. In Stockholm, for example, you need to book your ride at least 24 hrs in advance with the exact time and address for trip origin and destination. En route the driver may pick up and drop off more disabled passengers which may delay you considerably. Flexibility which most people require in order to work, to manage their personal affairs or to raise children has apparently not been a design criterion.

Post-Procrustean service delivery

Social policy has progressed since the days of Procrustes and today we see a growing number of services that have the following characteristics:

- the services are provided not in kind but in the form of cash payments to users

- with the funds users purchase services according to their preferences, from the service provider of their choice

- users have the initiative and control; they are empowered

Of the numerous Post-Procrustean services in existence I briefly describe the two that I am most familiar with, since I was involved in their origin.

Example 3: The Swedish Personal Assistance Reform of 1994, officially known as LASS. (3)

People with extensive disabilities are entitled to cash payments from the Swedish national social insurance fund. Needs are expressed in the number of hours of services per week. Assistance with personal hygiene, eating, communicating (in the case of non-verbal persons), household chores, assistance at work, getting around town or traveling abroad are to be covered.

The money from the National Social Insurance Fund pays for the assessed hours with all direct and indirect labor costs plus administration including the costs for accompanying assistants' travel, hotels and meals. The monthly payments are neither means-tested nor taxable but have to be fully accounted for.

With these funds the individual assistance user can purchase services from any service provider. About 70% of the recipients buy their services from local governments. Some 15% have organized themselves into user cooperatives that provide services. The remainder purchases services from private companies or employ their assistants themselves. Any combination of these alternatives is permitted.

Today, instead of putting up with the workers of the municipal home help services I am a member of a user cooperative to which I delegate all paper work and concentrate on recruiting, training, scheduling and supervising my staff. I have maximum control over the services which I receive, because I am the service provider. I am the boss.

With the municipal homehelp services in Stockholm I would have had great difficulties in pursuing a career, not to think of traveling and working abroad. I would have hesitated to get married. Because of the services' poor quality I would have depended too much on my wife. An equal, mutually supporting relationship with freedom for both to develop would have been impossible. Also, we would not have decided to have a child, since I would not have been able to take part in the practical aspects of parenting.

Example 4: "Taxi for All" a pilot project with mainstream wheelchair-accessible taxis (4)

Another example of a Post-Procrustean service is the Institute's on Independent Living pilot project "Taxi for All" in Stockholm County. In line with the Universal Design principle (5) a number of wheelchair accessible cabs run in regular taxi traffic. Wheelchair users can call regular taxi switchboards and order a wheelchair-accessible cab within 45 min.

Such mainstream taxi solutions exist in numerous cities in Europe and around the world. In London, for example, 100% of the taxi fleet is wheelchair accessible. In the UK and Australia legislation requires any taxi vehicle to have wheelchair access starting in 2004. Under such conditions there is little need for special services for disabled people. What is required are subsidy schemes that provide disabled users with purchasing power.

Comparisons

We return to Diagram 1. The dotted area, as you recall, denotes the gap between complete equality of opportunities for all members of society and the degree of equality of opportunities that is supported by the full application of the Universal Design principle. This gap needs to be compensated by individualized support services. But which type of services?

Post-Procrustean solutions have the following advantages over Procrustean services:

Procrustean services originated, when the medical model of disability was strong and services were typically provided in institutional settings. To view service users as passive objects without choice or control is not compatible with a modern interpretation of citizenship. To deny individual differences in needs and preferences is dehumanizing. Much of today's second class citizenship of persons with disabilities can be traced back to the self-fulfilling prophecies that Procrustean services give rise to.

Procrustean services tend to rely on centralized planning and monopolistic service provision. The 1990's showed that such systems are neither sustainable nor well accepted by the citizenry in the long run. For similar reasons public power and telephone monopolies are de-regulated today. Freedom of choice and increased efficiencies through competition can benefit also our sector.

From the user's point of view, the crucial difference between Procrustean and Post-Procrustean services is the individual's degree of control over funds, service organization, service operations and the resulting quality. For these reasons Procrustean services promote dependence and passivity, Post-Procrustean services provide conditions for individual self-determination and growth. The Swedish LASS reform has been called "the disability reform of the century". Whenever the government tried to introduce cut-backs, hundreds of persons with extensive disabilities demonstrated in the streets, in any weather, to defend the reform and the improvements in their life they have accomplished with it.

Procrustean services use resources less efficiently. They typically offer the user no choice but only one service bundle without the possibility of changing its contents. Here is an illustration: A special transportation user in Stockholm told me that his 30 km trips to work cost the local government € 60,000 a year. He would prefer driving his adapted car to work but cannot afford the gasoline prices. He offered the County Council a deal suggesting that they pay him € 6,000 a year in cash instead of delivering € 60,000 worth of services. But present rules do not allow such flexible solutions. (6)

In addition, Procrustean services require more administration than Post-Procrustean ones where users choose their degree of involvement in every-day operations. In the 1980's the Stockholm City home help service had 16 levels of hierarchy between the individual user and the top administrator. The 16 levels not only caused the users' powerlessness but also high administrative costs. In the user cooperative I founded there is only the cooperative's elected board above the user.

I do not argue that Post-Procrustean services are cheaper to the taxpayer. Cost aspects are secondary when it comes to human rights. But I think it can be shown that, at any level of expenditure, Post-Procrustean services deliver more quality as measured in terms of users' possibilities for self-determination.

Quality measurement is impossible when users have no acceptable alternatives to compare. For example, what does a 96% user satisfaction with the Stockholm special transportation system mean, where most users have no alternatives and the general population would never accept such an inflexible system? 96% satisfied users are reminiscent of the election results in the former German Democratic Republic. We know what happened when citizens there could vote with their feet.

The obstacles

One big obstacle to the introduction of more Post-Procrustean services are the users themselves. Many of us have been in Procrustes' beds for too long, have been mutilated and stunted, lost self-respect and self-confidence. They will need much advice, encouragement and many examples of other people in the same situation who took the plunge before. Here is an important role for organizations of disabled people. The Independent Living movement in many countries offers peer support groups to persons who contemplate changing to Post-Procrustean services.

Yet, often, there is no need to agonize over difficult changes, since in many direct payment schemes users can purchase services from any provider including their current Procrustean service agency. In Belgium, for example, institutionalized disabled persons are now free to turn their direct payments over to the institution or to use it to move into the community when they feel ready. The money follows the individual - not the agency. (7)

For that reason, the lobby of the service industry often opposes direct payment schemes. Since Procrustes' days they have had time to establish strong political positions. In Belgium, for example, from the end of World War II up to 1999 the Minister of Social Affairs had always come straight from Caritas, the NGO that runs innumerable institutions. During these decades, thousands of Belgian disabled people had to spend their lives in Procrustes beds. (8)

The service industry has had little incentive to depict us as responsible citizens. Negative stereotypes, exacerbated by media campaigns for fundraising, have made it difficult for politicians to support direct payment initiatives that assume recipients who can act in their own best interest and manage their own affairs.

The issue of direct payments vs. services in kind is infested with ideological landmines. Immediately, the questions of privatization and the role of the public sector are drawn into this political quagmire where service users' first-hand experiences carry little weight in comparison to party ideologues' abstract principles. A common argument against cash payments, for example, is the notion that only a strong public sector can guarantee general welfare. Most disabled service users agree that the state sets the regulatory framework including needs assessment criteria; that the public pays for the services, since we do not have the money or could otherwise not afford to be gainfully employed. But is the government always best fit to produce the services? Should not the citizens be entrusted to decide for themselves?

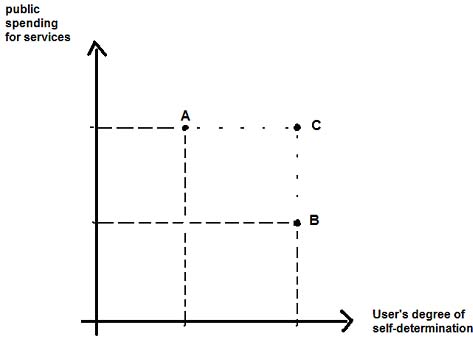

Diagram 2. Political parties' positions on public spending for services and user's degree of self-determination

Diagram 2 illustrates the political dilemma we find ourselves in. The vertical axis shows the amount of funds that political parties are willing to spend on disabled peoples' services. On the horizontal axis is the political parties' support for the service users' self-determination.

In Sweden, the conservative parties might support our self-determination and freedom under responsibility, provided it does not cost much. Point B denotes this position. The parties to the left are often willing to back up their solidarity with one of society's weak groups with money, but want to control the use of the money, as in point A. Service users want of course the best of both worlds, maximum funds and maximum self-determination.

To get to point C will take work and time. It will require allies in the form of service providers who understand how to win goodwill by supporting our cause for direct payments. It will require politicians who dare to translate their convictions into concrete measures against prejudice and for the implementation of human rights for all citizens. But most importantly, it will require that more persons with disabilities demand cash payment solutions as instruments for self-determination, and teach and support each other in how to use them.

As to the Independent Living Institute, we will continue designing pilot projects involving cash payments. It would help, if the European Social Fund's programs would be more interested in promoting services in our field. For example, there are still millions of citizens in present and future European Union countries who are warehoused in institutions. To get these citizens out and into the mainstream must be a priority. As long as we tolerate the inhuman treatment of humans elsewhere, we cannot feel safe in our relatively comfortable enclaves.

Notes

1. Among the services that the Institute's staff were instrumental in are

a) STIL, Stockholm Cooperative for Independent Living, a user cooperative, which served as model for the Swedish Personal Assistance Reform see Ratzka, Adolf D., The Stockholm Cooperative for Independent Living, Stockholm 1996, web publication www.independentliving.org/docs3/stileng.html.

b) the pilot project for the mainstream taxi solution in Bratislava, Slovak Rep see Ratzka, Adolf D., Direct Payment Schemes in Slovakia, Stockholm 1998, web publication www.independentliving.org/docs3/slovakia.html.

c) the personal assistance pilot project in Bratislava, Slovak Rep, ibid. which led to the present national direct payment scheme for personal assistance described in Repkova, K.: "Personal Assistance - a key towards independency in the life of people with disability in Slovakia", Disability Tribune, July 2002.

d) pilot project "Taxi för alla" ("Taxi for All") see Swedish description in www.independentliving.org/taxi/index.html (in Swedish).

2. See Ratzka, Adolf D.,"Independent Living and Attendant Care in Sweden: A Consumer Perspective, World Rehabilitation Fund, New York, Monograph No. 34., web publication www.independentliving.org/docs1/ar1986spr.html

3. Brief description of the Act www.independentliving.org/docs1/ratzka1998lass.html

4. Independent Living Institute, www.independentliving.org/taxi/index.html (in Swedish).

5. For the "Principles of Universal Design" see Center of Adaptive Environments, www.adaptiveenvironments.org/universal/index.php

6. Gary Horneus, Märsta, Sweden personal communication June 2000.

7. Jan-Jan Sabbe, Gent, Belgium personal communication October 2002.